What You’ll Learn:

In this episode, hosts Catherine McDonald, Andy Olrich, and guest Hugh Alley discuss how crucial it is to identify and develop effective leaders in today’s dynamic business environment.

Training Within Industry (TWI) offers a systematic approach to building foundational skills that not only enhance operational performance but also cultivate leadership potential.

About the Guest:

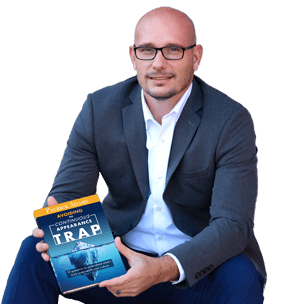

Hugh Alley is author and consultant. He divides his time between coaching senior operational leaders in continuous improvement, training front line leaders in core supervisory skills, and designing industrial facilities. Trained as an industrial engineer, he has run three manufacturing and distribution firms, and a department in a government agency. He has taught skills to over 1,000 front-line leaders. He has written two books: “Becoming the Supervisor: Achieving Your Company’s Mission and Building Your Team”, and “The TWI Memory Jogger”. He speaks frequently about supervision, quality, lean manufacturing and Toyota Kata. From his home near Vancouver, Canada, he helps clients across North America.

Links:

Click Here For Hugh Alley’s LinkedIn

Click Here For Hugh Alley’s Book: Becoming The Supervisor

Click Here For More Information On First Line Training

Click Here For Catherine McDonald’s LinkedIn

Click Here For Andy Olrich’s LinkedIn

Andy Olrich 00:00

Hello and welcome to the Lean solutions Podcast. I’m joined today by our host, Catherine McDonald and myself. Andy Olrich, how are you, Catherine,

Catherine McDonald 00:39

I’m very well Andy. Andy, how are you?

Andy Olrich 00:42

I’m going good. Going good. It’s, it’s pretty cold down here. It’s our winter time at the moment. How’s things up there? Where you are in

Catherine McDonald 00:48

Ireland? Ah, summers just started in August. Believe it or not, we’ve, we haven’t had a summer up until now. So, yeah, loving it, actually, loving life at the moment. It’s great. It’s

Andy Olrich 00:57

really sounds lovely. Yes, it’s jackets and raincoats here at the moment, so I wish I was there. So yeah, really excited. Great to catch up again. And today we’re going to be talking about twi to identify and develop leaders. So what is twi training within industry? So I’ve got a really great guest on today, and we’ll talk a little bit more about him in a moment. But really around, you know, today’s dynamic business environment, identifying and developing effective leaders, it’s it’s crucial for that organizational success, and Twi, it really offers a systemic approach to how we build foundational skills and also, not only enhance the business performance, but also how we can really develop and cultivate leadership potential within our people. So I’ve done a little bit of training and learning in this space, but certainly not on a level like our guest today. And our guest today is Hugh alley, and I’ll throw to you. Catherine, tell us a bit more about Hugh.

Catherine McDonald 01:54

Yes, so Hugh Alley is an author and a consultant. He divides his time between coaching senior operational leaders in continuous improvement, training frontline leaders in core supervisory skills and designing industrial facilities. Trained as an industrial engineer. He has run three manufacturing and distribution firms and a department in a government agency. He has taught skills to over 1000 frontline leaders. He has also written two books called The first one’s called becoming the supervisor, achieving your company’s mission and building your team. And the second one is called the TWI memory jogger. He speaks frequently about topics like supervision, quality, lean manufacturing and Toyota catta, and from his home near Vancouver, Canada, he helps clients across North America. So welcome to the show. Hugh,

Hugh Alley 02:50

thank you so much. Catherine, delight to be here.

Catherine McDonald 02:54

Great. Good stuff. Good stuff. Well, we’re delighted to have you here and this. Well, it’s a new topic for me. Twi, as Andy said, training within industry, as in, I haven’t been a host on the show where we’ve discussed this topic, and I’m really interested to learn a little bit more. So would you maybe start us off you by telling us a little bit about twi and where this whole concept maybe came from, and what it means. Sure,

03:18

I’d be delighted to so twi started, really around the start of Second World War, when the US military was looking around and recognized that they had three major questions they had to add to answer. One was, how on earth are we going to train people, as many people as we need, as fast as we need, to meet the needs of the war? Because they could see impending skill shortages, and that’s the link to today, right? Is skill shortages. The second question they had was, how are we going to develop some of these raw people into leaders, to become supervisors and effective at it, because many of the people in those leadership roles, maybe only had four months more experience than the people they were overseeing, so that made it pretty rough. And the third question they had was, how are we going to make the best use out of the equipment and the materials they had? They had shortages of everything, steel production facilities, everything and and so how do we make the best use of that? How do we deal with the fact that we’ve got a shortage of people so that we can be as productive and as efficient as possible? So those were the three starting questions that they had. And to give you a sort of an example of the scale they were dealing with at the start of the war, if they wanted to train. A lens grinder. So, you know, guns needed lenses for sighting. It turns out that the conventional approach to training a lens grinder was that it took five years. And they kind of looked at each other and said, Well, if it’s going to take that long, the war will be over and it’ll be done. And so they said, We got to fix that. And and to give you a sense of the scale, in the in 1939 in the US shipyards across the country, they had 50,000 people working in all the shipyards. And three years later, they had 650,000 people, so a 19 fold increase, and that’s the scale they were coping with. And so they really had to deal with, how do we get supervisors? How do we get the skills? And that’s what they developed. By the time they got to the end in 1940 they’d actually figured out how to train a lens grinder in about five weeks. And and there was, there are stories that some companies got it down to five days. So that is pretty remarkable.

Catherine McDonald 06:20

So born, born out of urgency, but exactly, yeah, but there was something to that. Because, like us all, when we light a fire under us, we can do great things more than we ever realized we could. Isn’t that, right? So, yeah, okay, yeah, this sounds really, really interesting. So it’s a different, a different way to train because, and you can tell us more about it in a minute, but it’s a different it’s different to the traditional style because there’s a lot more structure to it. There’s a lot more planning involved. There’s a lot more hands on practical work, isn’t that? Right? It’s just, it’s it’s different how training was done before that, and obviously it’s different to other training that exists out there as well. That’s right.

07:00

And if you’ve been in in any kind of organization and watch the training that happens, the most common thing that happens is that you have one person you know showing the per the new person, maybe once, if you’re lucky, and then figure it out, right? And you’re just setting that person up to fail. You’re setting them up to make mistakes. And other times, you’ll just have a somebody, whoever’s doing the training, just watch me right, not even really explaining what they’re doing. And you just have to think about any new skill you’ve learned, and when you’re watching it for the first time, you don’t even know what you’re looking at. And so the conventional approaches of telling or showing on their own, just they don’t cut it. And Job instruction deals with that and that. It uses a four step method that is consistent throughout the TWI programs, that makes it really easy to learn.

Andy Olrich 08:21

Fantastic. It’s such a significant case study, obviously, around how a very significant burning platform can get people to really narrow in and go, Okay, we just can’t do it that way anymore. You know, how are we going to to rise above it? And we’ve got a very famous doctor down here on television. He’s called Dr Carl. He’s been on for years, wears very loud shirts, so very bright, colorful. And I was watching him a couple of years ago, and he talked about the US military, and in particular around the building of airplanes and during the war. And it was something like that. Only the United States had only built 300 airplanes prior to World War Two, and then at the end, they’d built over 300,000 in quite a short amount of time. And I always think back and what stuck with me when I was really getting into lean and I had a really great trainer, and when we talked about standard work, and twi Rosie the Riveter, so there’s that image of Rosie with the spanner, we can do it. And because I had to mobilize that the women in the workforce, which wasn’t traditionally done back in the day, and how it really that image really sticks with me about how we can, when we need to, and really just empower bring anyone from any part of the world, and we can bring them in and give them some good structure standards and and get it done and probably in a better way be. And I’m such a visual learner, so most previous places I’ve worked like training David, Ah, here we go. This is, this is another snooze fest, because it was all paper and someone would just be up the front talking. And, you know, it’s a bit better now with videos. But I. I was like, take me out there and just show me, and let me do it, and just, just give me a hand. So I I’m absolutely a, yeah, a real fan of it. And that story, it’s pretty compelling and pretty hard to look away from when you are trying to engage people to maybe have a look at this approach. So great example. And I’m a bit of a war history buff too, so I just love the connection there as well. As challenging as that time was, we can do some great things if we need to. And I think you know how with those twi skills. So we’re taking this approach and we’re bringing that into the organization, from an organizational perspective. Q Can you talk through how that performance lift or that real step change can be achieved, and some examples of what that looks

10:42

like, sure, sure. So if you think about it, where you know, leaders have, you know, I think about it as two fundamental responsibilities. They have to achieve the mission of their organization, and they’ve got to look after their people. And you can’t have just one. You got to do both and and the you, because leaders can’t on their own achieve the results they’re after, right? You can’t ship products by yourself. You need your team doing work with you. And so you need the leaders able to foster great performance within their team. And so Job relations, which is one of the three programs, gives some structure and tools for a supervisor to do that, and the results can be really remarkable. So let me give you three examples. Was working with a company that made gas appliances, and there they were facing a 60% annual turnover in in people, which was that’s really expensive, it’s very difficult to perform when you’ve got that. And I in the in one of the early meetings with the company, one of the supervisors said, Well, the thing is, I just don’t know what to do when somebody doesn’t perform, so I just fire them. And I’m thinking, what? And and one of his colleagues said, Yeah, that’s the way we deal deal with it. And well, of course they’re going to have turnover like that, if that’s your reaction. But they the key was his comment that I don’t know what to do, and that’s so often the case that you know people, they’re they’re good at their work, and then they get thrown into the role as supervisor or team leader or whatever, and somehow they’re expected just because they’ve got the label that they’re going to be able to do it, and it just doesn’t work. That particular company. We train them in the job relations program, and in four months, their turnover was down to 10% and you start thinking about the impact of that for the company in terms of being able to deliver product on time reduce their costs was huge. And, and that was just, you know, it’s, it was a 10 week or not even 10 week 10 session program over five weeks, and that got that kind of result.

Catherine McDonald 13:46

And that’s, this is really interesting, you so the how behind this are you teaching, you know? So this is one of the programs within Twi, this kind of job relations, okay, so in these weeks, are you teaching skills. Is there a practical method? Is absolutely there, role play? Is there? How? What does it involve to get that point where relationships actually change as a result of this program? So,

14:11

so let me give you a couple of simple examples of the kind of micro skills that people need to learn the in within job relations, they identify four foundations for good relationships between supervisors and and their their team, and those are, let people know how they’re doing good and bad. Give credit where it’s due. Let people know in advance of things that are going to change them and make best use of everyone’s abilities. So in this particular company, I said, Okay, folks, your first homework, if you will, is but each day you know, this afternoon, tomorrow, next day before. Our next session, want you each day to go and find one person in your team and tell them what you’ve noticed about how they’re doing. And these guys were terrified about the fact that they were going to actually have to go and let somebody know that they were doing a good job. And it’s like, really, that’s a problem. Oh

Catherine McDonald 15:22

yeah, it’s still a big problem. People just have struggled to say these things, yeah. Go on, yeah.

15:27

Just, just go and say, Gee, I really appreciated that you took the effort, extra effort, to get that one done before the break, or whatever it was, you know, just little things. The supervisors came back. They were their faces were glowing because they had no idea they were going to get such a positive response. But that’s a really practical micro skill of giving somebody feedback. A second example of a micro skill that you need to learn is in Job relations, when you’re faced with a problem, the first thing to do is to actually figure out what your objective is. And so one of the the micro skills is, how do you set an objective for the behavior you’re looking for from your team member. And so you start thinking about, you know, how does it tie? How does this objective tie to the mission of the organization in terms of the results you need to get? How does it tie to the specific, specific observable behavior that you’re looking for and and how fast do you do? You need to see this happen. So you know those are simple things when you say them like that, but if somebody’s never been asked to articulate it. Then it gives them, all of a sudden, a tool for them to say, well, actually, that’s what I want. It’s not enough to say, well, I want that person to be more of a team player. What does that mean in behavior? What am I going to see? Yeah,

Andy Olrich 17:20

it’s so isn’t, doesn’t that sound crazy though? Like, it just sounds so simple in a way, in a way where it’s like, go out and recognize a good job. Like, say thank you. We don’t do that enough, and just give me some why? Like, why is this important? Like, thank you, and let me know where I fit in. I mean, that that’s something that we should just innately do always, but yeah, we actually have to sometimes work hard and put that structure in a discipline to say, Have you done that today? It sounds, it does sound a bit crazy when you think of it on the surface, but that’s just how we are. So it’s, again, it’s a really good opportunity, as you said, to to formalize that. And that’s how give them more clarity on Well, what do we mean by more productive or a good worker and things like that? Yeah. Yeah.

Hugh Alley 18:09

Go ahead. Catherine,

Catherine McDonald 18:10

was just going to say that it’s that it’s leadership, like it is leadership. It’s just their leadership skills to be able to give feedback, but not just give feedback to be able to inspire and motivate. You’re building in all these skills. It’s not the simple act of catching someone doing and saying something to him. You’re doing much more than that, and it’s leadership, really. So, yeah, I love that. Yeah,

18:28

another example of the kind of results you can get. So a client, they’re doing fairly complex electronics assembly on very small items. These are these items ranged in size from maybe two centimeters long to seven or eight centimeters long, an inch to four inches, if you want to work in Imperial and it took this company 12 weeks to bring a new person on board and get them up to speed to assemble that product in a solid way. And it was a very seasonal business. So every year they were faced with bringing on a bunch of people and taking three months to train these people up. And so what we did is we taught the supervisors in the company job instruction, and at the end of that process, they could bring a new person on board and have them producing at productive speeds, correctly in four weeks, down from 12 weeks, like the savings from that somewhere on the. Of 20 to $30,000 a person that they brought on board, and as important, what they found is their scrap rate went down too, because the way job instruction works, there’s enough repetition in it and enough oversight in those early repetitions that people get it right, get it correct from the start, and so you didn’t have $600 chips getting smashed or or, you know, soldered incorrectly and having To be tossed so that the savings were huge. And they also discovered that with that new approach, they had shortened their new product introduction by three months, which is huge.

Andy Olrich 20:55

I think to, I think to down here we have traditionally three month or six months probationary periods for new employees. And I think, you know, you’re putting them into training for three months, and then it’s clear, for whatever reason, that maybe they’re not the right person. That’s a that’s a big investment and waste of time, just,

21:19

yeah,

Andy Olrich 21:20

you know, like, I think that the opportunity there to put them to work and give them that more hands on, it saves a lot of time and again, the recruitment cost of then replacing that person, etc. It’s, it’s a hit, it’s a massive opportunity,

21:35

yeah, and it, it’s, goes far broader than just, you know, assembly or manufacturing world, I have a client who use the same approach for designers, steel designers. So these people are making complex structural steel products, and they use the job instruction model to let them reduce the time it took to take somebody off the street and turn them into a decent designer from two years down to eight months. That was huge savings for them and and the people who were learning it, they felt valued and appreciated and felt like they were contributing much faster, and that tended to reduce turnover. I think that’s

Andy Olrich 22:36

a powerful point, because we don’t hire people just phrase it that no nothing. They’ve got skills, capabilities that they bring to the organization. And then, if there’s the the faster you can complement those skills, capabilities and ways of thinking to how what you need them to to bring and learn at your organization. I think they would feel great, because they’re not sort of being turned right back to feeling like they’re being walked right back to zero, that they can get in and they can immediately start to add value in that innovative culture and mindset around the quick, the more agile approach, and we we turn things over a lot faster. And there’s a, it’s just such a another great example. Thank you.

Catherine McDonald 23:16

Yeah. And actually, that makes me think I look at leadership. I suppose I’m starting to look at a little bit differently, because I’m in it for so long. And I do believe that people start a job for the 99% of people full of enthusiasm, you know, they want to do a good job. They are internally motivated. They’ve chosen to take this job. And I sometimes think the role of leadership is not to motivate people, because we can’t really, you know, but it’s not to demotivate people. So everything we do should be not to demotivate people. It should be to help keep their motivation up. So if we can give them the right instruction and clarity on how to do their job, the right way to do it, you know, mistakes happen, but to prevent mistakes as much as possible and to give them confidence, that’s what we should be focusing on, isn’t it, really to help people stay motivated.

Hugh Alley 24:02

Yeah, and I just see that time and time again in in the people that that learn these skills and and sometimes these are people who’ve got lots of experience. I a guy that I know who he’d been a supervisor for 20 years and went through job relations, and his reaction was, this, was this the the single most important training I’ve ever had, and why did it take 20 years for me to get it?

Catherine McDonald 25:10

So, we’ve got two different programs that you’ve mentioned, job instruction and job relation, so companies might avail of one or both. Or how does it work? Or there’s another part to it as well. Well,

25:21

there’s another part called job methods, and it’s around making improvements in the actual process of the work and optimizing that. And again, it’s a very structured thing that, you know, I had one guy who was learning that, and by the time he was finished, he had a crew of six, and he’d figured out how he could do it with a crew of five. So he freed up one person who could then go and work somewhere else in the plant. And as it turned out, that particular plant, they had a bottleneck that could absorb the new labor. And so all of a sudden they got a product. Not only did they get a productivity gain because they doing it with five instead of six at that operation, they got a production gain because they added to the capacity the plant. But this was a very ordinary guy who had had, you know, he’d grown up making, doing paint, and he had no particular leadership skills other than getting trained in this job methods, and he was able to tear apart the work and put it back together again and make go, make some trials, and do some trials and and find a way that he could simplify the work enough that that he got those kinds of productivity gains

Andy Olrich 26:58

was massive. Yeah. And using this approach to identify potential leaders and and developing those skills. So,

27:08

so I would, if you’re trying to identify leaders, I would start by having people do learn to be to do the job, the the instruction, to start with job instruction, because you can see when you’re watching somebody teach. You can see whether they care about the people that they’re teaching right, or whether they just want the status of being the instructor. You can tell whether they are listening and watching and observing the people doing the work to be able to give them good feedback, or whether they’re just kind of going through the motions. And that lets you identify the people who are going to be good leaders who both look after the mission of the organization and look after their people. So So I look at that as if I’m going to pick somebody to see test out. Could they be a leader? Let’s get them instructing. First give them the skills to instruct and see how they do with that, and then make a call about, okay, are they ready to take on something more?

Andy Olrich 28:35

It’s great that this approach gives them, that you know, some tools, and that standardized approach. You know, you basically giving them how you would like them to teach and and lead within the organization. You know, throwing them in the deep end, and they will see what they got. So, you know, simple within that, maybe some of the tools associated with that so that you commonly use you so job breakdown forms or similar. And could you talk a little bit about, you know, what are some of the things that we would set those new people up with to get them going?

29:07

So there’s the fun. There are, I guess, three elements of any good instruction, right? You need a timetable and sort of a training plan, if you will. You need the job breakdown for the specific job, and you need a method of instruction. And so Job instruction gives you each of those, gives a way that you can track the skill levels of your team and and plan out where are the gaps? You know. You know what’s going to happen when, when the two of you go on vacation. You know what happens then? And I need to know that I can still run the. Land. So, gee, I have a gap, because if they’re both gone, I’m I’m missing a skill here. So now that helps me pick where, where to start. The the job breakdown process depends on or is, is built around the idea that there are three kinds of information that you include in a job breakdown. There are the important steps, the key points and the reasons, and so the important steps are kind of what you think is, what’s the next thing you have to do? The key points are, how do you need to do that? So it’s done right? And the reasons are, why that way? Like, what’s the consequence if you do it some other way? You know, Does, does the world go kaboom, or, or, or does a kid fall off a a balcony? Or, you know, why is, why does it matter? Because people like to know why, and if they know why, they’re less likely to shortcut. And then the the method for instruction is around repetition. So you know, as we’re recording this, the Olympics are going on, and you think about how often those athletes have to perform those things in their practices, right? The swimmers who just practice their starts and start and start and start, and they do all these repetitions, and they’re the best in the world, there’s some really good evidence that you need to have eight or 10 repetitions behind you before you’re capable of operating at an okay level. And so the instructional process in Job relate. Job instruction builds that in so that there are you layer in the information with repeated demonstrations, and then you have the learner do the task repeatedly as they layer that information, giving it back to you, which lets you know that they’ve learned it. So that layering really helps. I

Catherine McDonald 32:27

can see, so I know we’ve talked a lot about new people and new hires coming in, and how this benefits people who are new to a job, but I can see how this all links to continuous improvement as well, because when things change and we have one in existing process, and then we decide, you know, as a team, we could do better. And everybody says, Yeah, that sounds great, but then you have to teach people how to maybe do something differently or adapt their behaviors. So isn’t this really relevant to continuous improvement as well?

32:53

Totally, totally, or to new product introduction, right? You’ve got a new product. It has new processes. You got to train those too.

Catherine McDonald 33:04

Okay, so we often talk about the Lean tools, like value stream mapping, process mapping and and we talk about Kaizen, obviously. So there is kind of an overlink between this or I guess twi fits into how lean, how an organization becomes lean. Would that be fair to say? So a lot of this so job instruction, job methods, job relations, it is done within lean, but this is maybe a more structured way than some organizations would be used to when it comes to becoming lean organization. Yes,

33:34

there are a number of folks that have, have actually made the case that TWI is really the foundational set of skills for for what we call lean. The interesting story here is that after the Second World War, the people who had developed twi actually went over to Japan and Germany and helped with the reconstruction. And so they were, they were teaching these twi using these twi methods for training in those countries and little companies like at the time, Panasonic and Mitsubishi and Sanyo and Toyota all learned these skills, and interestingly, they did they while they were largely neglected in North America when Toyota was working with GM on the numi plant in California trying to set up their first joint venture. They said, This is how we want to train people. And the American people said, Oh, gee, that’s never going to work in in the US and and the one of the Toyota Exactly. Natives brought out the original English copy from the US, war power, war manpower commission, and said, No, that actually came from you guys. And that was the start of, sort of the resurgence, or the RE awareness of Twi. And no, not,

Catherine McDonald 35:22

did you know that? Andy, that’s fascinating.

Andy Olrich 35:24

Yeah, we ignored the Japanese miracle. So we down here in Australia, obviously, through the war, anything that had Japan or the culture or anything like that, we were very much against it, wouldn’t even get a second thought. And it was really through the larger multinationals from the states that started bringing this in, and that’s when we really, actually had a bit of a look at it. And yeah, but that’s what it all came back from in Australia, unfortunately, too, when we do some innovations, we’re really good at creating and innovating things. But then the uptake, or the that deployment, it usually goes somewhere else, and then they develop and make a really good dollar off it. And that’s what I say to people like this, a lot of these things, it’s not we, it was taken over there and used in Japan, but it’s foundations were from a lot of stuff in the western side. We just kind of missed that. And we just somebody gave me the term. He was an American, and he said, after the Second World War, and I mean this with the greatest respect, was his words, not mine, but he just said, you know, we got fat, dumb and happy, and that’s what he said, not me, right? And he said anything, we just couldn’t get our heads around why Japan and all these other countries were just powering all these things through. We just thought, Oh, it was, you know, it was just that they forced them to work harder. And he said, when you actually peel it back and actually had, it looks like we used to do all this stuff, and we used to get even young people, kids, our wives, whatever, they all jumped in and got trained up in no time. The things they’re talking about, we just kind of thought, well, we didn’t really need that, because we were kind of number one again, that was his words. And now that’s what I say to people with this, especially with the the job breakdown form, as opposed to a standard worksheet like it gives you that why that we talked about before it so? Because if you don’t, and I find that’s a real gap with some safety, like an isolation plan, or things like that, well, yeah, we don’t do that a lot. We should have in there. It’s because if you don’t lock this thing out, we say it, but just having that and, and I love the the power it gives you to have consistent training. And we always used to say, look, we need, I need to know. The end result is, I know that. You know and, and it’s about, I can have any of my leaders go out and train whoever comes through the door next week. I’ve got more confidence that they’re being trained in a consistent manner. So it’s not just, Well, I was trained like this, but this is kind of how I do it. Fantastic. Auditing process. All that is Catherine was talking about the continuous improvement again, a foundation to go. Okay, that’s kind of how we’re doing it. Now, this person’s new, but they’ve identified a better way. Alright, how do we then standardize the training, etcetera, etcetera. But yeah, and that’s what from a cultural perspective down here, was, as I said, anything post war that had any sort of Japanese flavor to it, we’re like, no, not interested. Doesn’t matter. And really, great example. Yeah, it did. It’s funny where these things start and then have I come back again, isn’t it?

38:21

Yeah, so I really do think that, you know, a lot of the lean stuff is set up the way it’s so conventionally presented. It winds up being the Lean Expert who comes in and leads the Kaizen event, or is the is the CI person? And what happens, of course, is that then people wind up saying, Oh well, that that’ll get dealt with by the CI person when they come here, as if it’s not part of their responsibility as a leader, whether they’re at the team leader level or the supervisor or the foreman or whatever, but it gives them an out, if you will. Whereas the job methods, job instruction, job relations, all say, no, no, no, no, it’s it’s your job as that frontline leader to find ways in your little air corner of the world to make things better and easier for your people. It’s your job to make sure they can get they’re doing it correctly. It’s your job to make sure they’re actually following that standard work. And here’s the instruction way that you the instruction method you can use to get that and so I think it puts responsibility back on on the frontline leader. And because. Of building the relationship, that supervisory relationship with your team, and that’s supported by the job relations model, then you’ve got, you can actually have a cohesive team that is working to make things better all the time.

Catherine McDonald 40:21

Yeah, yeah. It hits on just the most important points, doesn’t it? So it’s the involving people in the identification of how your work your processes can be done better. So it’s involving people, then it’s putting a structure on the best possible way to do things and training people and how to do it. And then it’s also looking at the relationships and the dynamics between people, and understanding the importance of all of that, in order to stop relationships being a barrier, but to be able to have effective relationships, to make sure that, you know, the processes will work, you know, and people are mooting that. So, yeah, it’s excellent. It’s It’s amazing. You’ve broken it down really well. great. Um, what is, do you think the starting point? So if somebody’s listening today and they want to know, wow, I’m really interested in this. We don’t use this. Twi never even heard of it, maybe, where, where? What do they do next to

41:16

so it’s a great question, Catherine, and I think the what I’ve wound up doing is saying you’re going to start in one of two places, either with job instruction or job relations. And the question is, which one job methods is, I think, very much sort of the next step down the road, because if you don’t have a way to teach people, then once you get a new method, how can you actually put it in place? So you got to have the job instruction there first. So then the question is job instruction, or job relations? And I look at five things in the workplace. I look at who does the problem solving? Is it a is it more the employees or more the leaders? How many grievances Do you have, right? If you’re in, you know, if you’re not a union shop, then you know, what’s the level of discord? You know, how many complaints is HR getting because if that’s high, then that’s probably an indication there’s an issue in the relationship between the frontline leaders and their people. What’s your turnover level? You know, 5% is kind of normal, but if you’ve got more than 10% turnover in a year, something’s wrong. There’s a sort of spidey sense should be going are there? Is there? Are there indications of bullying or blaming in the workplace? What happens when somebody makes a mistake? What’s the what’s the institutional response when someone makes a mistake? And the last thing I look look at is, where are the improvement ideas coming from? Are they coming from the employees? Are they coming from frontline leaders or from the boss? You know, the big bosses. And by looking at those five things, they’re just useful indicators of whether the supervisory relationship is solid, because if the if that relationship is not solid, it’s there’s no point in doing job instruction because they won’t listen. They won’t care, because they’re feeling disrespected. A good friend of mine, skip Stewart comment, and He’s the VP of improvement and quality, I think at Baptist Memorial Health in Memphis. He says Job relations is the best way to operationalize respect for people. And I love that saying he says it better than I did, but it’s a wonderful comment. And if that’s if that respect for people isn’t there, then there’s no point in doing the other stuff, because it just won’t stick. So so I use those five markers, if you will, yeah, as a way to understand is there enough fundamental Respect in the workplace that you can move on to Job instruction. Or do you need to start with job relations? I worked in I remember walking into a plant, and my spidey sense went on. There’s something toxic going on here, and we. Started with job relations, and it made all the difference. And we wound up training not just our leaders, but all our core staff in Job relations so that, so that they understood what they could expect. And we were very clear about what we were expecting in our in our relationships with people, we got an immediate 10% lift in productivity from that.

Catherine McDonald 45:29

I joke I get so much because a lot of the time right. I might go in as a lean consultant, but I turn into a leadership coach, because we can’t actually become a leaner organization until we have the leadership skills, people and teamwork working together. So I get that 100% get why you would focus on relationships. Andy, I know you’re probably won’t ask a question, but I’m dying to ask this. How Go,

Andy Olrich 45:51

go, go, go.

Catherine McDonald 45:52

How do we know when we have enough work done on the job relations piece to move on to the job instruction piece? So how do we is there another kind of gap and at scope, or something we do to find that out?

46:09

So if, if I’m trying to instill job relations as the kind of way we do things here. Yeah. Then as a manager, when I have one of my leaders coming to me with a problem, and they present it to me in a form that I can see they’ve walked through the job relations process, then I’m going to be comfortable that that that’s in place. But if they come to me and just say, Catherine, you gotta do something about Joey, right? Okay, they’re not ready, you know. So when, when they can come to you as the manager, having already articulated, you know, I’ve got the facts, and I’ve been weighing and deciding, and I can’t decide between these two things, but here’s my thinking about it. Now, now I can hear they’ve actually done the work. They’ve been paying attention. They’re using the model. And you know, anybody who spend any time working through a bunch of factories or any kind of business organization, you can almost smell it when there’s respect versus when there’s not right, it’s like the spidey senses work. And, you know, this is a toxic place, or it’s or it’s a really healthy place, and and so I want to see the health start to return.

Andy Olrich 48:01

That’s that was a was a great Catherine, I’m glad you went. That was a fantastic question. And some insights there. And there’s a lot of studies and proof that people will stay at an organization if the training is of a higher standard, and it’s done well, and they continuously learning. A lot of people are prepared to take less pay to to work somewhere where they really get that rich development, and they feel part of that, and then the joy you get from training others and passing on your your skills and knowledge, but in line with what we that around it, we’re clear on what we expect. So I thought that was, yeah,

48:37

I had that exact thing happen to me. You know, I came in, we did JR and and and I heard that there had been a number of people who had left the company because they didn’t like the the environment. And about 1824, months after I got started, and we got this in place, we started having some of those people come back, and we because they’d heard, you know, they were still in touch with their buddies who worked for the company, and they’d heard about the change, and we knew they were taking two bucks an hour less to come back to the company because they weren’t really happy where they were because they didn’t feel they were being treated respectfully.

Andy Olrich 49:31

Fantastic. Hugh, this has been a really great chat. I’d love to catch up again in the future and talk more. It is such a foundational piece around culture and success, and we really thank you for for coming along today and chatting to us. And if people want to find out more, you’ve got first line training website. You’re in Canada. Yeah, I am, yes. What’s some of the ways that people can reach out and get in touch with you?

49:57

I’m on LinkedIn and our. Active there. That’s probably the easiest way the there’s a website for my book becoming the supervisor that’s becoming the supervisor.com there. There’s a bunch of if people sign up, there’s a bunch of downloadable information there that they can draw on. And, yeah, I think LinkedIn is the easiest way to for people to to find me.

Andy Olrich 50:30

Well, everybody listening? Yes, certainly I have, and I will continue to check out Hugh’s work and his book. So Catherine, some final words from you. Yeah,

Catherine McDonald 50:40

this was just really interesting. I mean, I’ve heard of Twi. Never really understood it in depth. To be honest, I have went through how many different studies in lean, lean black belt, you know, it’s not really feature. And I’m really, really glad you’ve informed me and enlightened me about all of this and the history and how it’s informed lean. And I feel a lot more educated after listening to Hugh, and I’m actually really interested to look into twi a little bit more and what it means to be a trainer, and I’m really interested. So thank you. I’ve really enjoyed it. Great.

51:13

So glad that you did been a fun conversation.

Andy Olrich 51:16

Yes, yeah, great. Okay, well, thanks everyone. We’ll catch you all next time. Take care and see you later.

Catherine McDonald 51:23

Thanks, Andy.

0 Comments