What You’ll Learn:

In this episode, hosts Patrick Adams and Shayne Daughenbaugh discuss the implementation of Lean principles in accounting, emphasizing simplifying cost accounting, aligning costs with value streams, and adopting a PDCA mindset, while also noting the limitations of traditional practices and the need for a value-based approach. They covered Lean pricing strategies, such as market-based pricing and demand alignment, and discussed optimizing changeovers for efficiency, alongside sharing experiences of assisting veterans in their transition to civilian life.

About the Guest:

Mark DeLuzio is Founder and Chief Executive Officer of Lean Horizons Consulting. He is also a former Corporate Officer and Vice President of Danaher Business System (DBS) for Danaher Corporation. Danaher has been recognized as the leading implementer of Lean globally and has been rated as the 3rd most profitable US stock over the last 30 years. Mark is also credited with developing the first Lean Accounting process in the United States for Danaher’s Jake Brake Division, where he served as their Chief Financial Officer. Mark is the author of “Turn Waste into Wealth,” which offers practical advice for those considering a Lean transformation and “Flatlined – Why Lean Transformations Fail and What to do About It”, which offers the lessons learned from Mark’s association with hundreds of Lean transformations on a global basis.

Links:

Click Here For Patrick Adams LinkedIn

Click Here For Shayne Daughenbaugh’s LinkedIn

Click Here For mark Deluzio’s Website

Patrick Adams 0:00

Welcome to the Lean solutions podcast. This is the podcast that adds value to leaders by helping you improve performance using process improvement solutions for bottom line results. My name is Patrick Adams and this season I’ll be joined by three other amazing hosts, including Katherine McDonald from Ireland, and already from Australia and Shane Daughenbaugh from the United States. Join us as we bring you guests and experiences of Lean practitioners from all over the world. Hello, and welcome to this episode of the lean solutions podcast. My name is Patrick Adams and I’m joined by one of our second hosts Shane Daughenbaugh involved Welcome back Shane for another amazing episode with an amazing guest Steve, how you doing?

Shayne Daughenbaugh 0:45

I am doing well. It is it is bring currently at the recording of this. So this is the time that my heart is happiest. Love this time of year so I’m doing well thank you love it.

Patrick Adams 0:57

Well today we are joined by our guest Mark Deluzio and Mark is the founder and chief executive officer of Lean horizons consulting. He’s also a former corporate Officer and Vice President of Danaher, bit of the Danaher business system for Danaher Corporation Danaher, if you’re not familiar with Danaher, they have been recognized as the leading implementer of Lean globally in many different aspects, and they’ve been rated as the third most profitable US stock over a 30 year mark. But Mark is credited with developing the first lien accounting process in the United States for Danvers Jake brake division, where he served as their CFO. Mark is also the author of turn waste into wealth, which offers practical advice for those considering a Lean transformation. And then also, he authored flatlined, why Lean transformations fail, and what to do about it, which offers some lessons learned from Mark’s association with hundreds of Lean transformations on a global basis. So we have an expert in the midst, and we’re excited to dive into a topic here with Mark first mark, I want to welcome to the show. So welcome.

Mark Deluzio 2:08

Glad to be back, guys. Yeah, no, thank you. Yeah. And I’ve noticed Shane taken on a new role with you, Patrick, and the listen to your podcast. And it’s been fun to listen to all this. So you guys are doing a great job. Keep keep doing it.

Patrick Adams 2:22

Well, I appreciate that. I was I went back to you were on the show mark, back in season two. And I was listening to that episode myself, just catching up on the Danaher business system and some of the conversations that that you and I had. And as I got to the end of the episode, we said, hey, this Lean Accounting thing, or traditional accounting problems with traditional accounting, why Lean Accounting is so important. We said, We need to get back together and do another whole episode, just specific to traditional accounting versus Lean Accounting. And I’m like, we never had Mark back. So here it is, we’re finally back together, I

Mark Deluzio 2:58

will tell you this metric. If you’re listening to my podcasts, you should see a sleep doctor, you must have sleep apnea or something to try to get to sleep. Anyway, no, no, that’s true. Yeah, we did say that. I do recall that. So glad to be back and help you guys out and get them get the message out. Right? That’s we’re trying to do.

Shayne Daughenbaugh 3:18

I’m excited about this topic, Mark, because I really know nothing about it. So if you could for those of us that are, you know, new to the room here in this space of Lean Accounting, can you give me kind of what’s the difference between traditional cost accounting and lean accounting? I am not a a in accounting, banking money expert whatsoever. I pay people to do this kind of stuff. So give me an idea of, of how this is different. What’s with Lean Accounting?

Mark Deluzio 3:50

Well, first of all, embarrassingly, Shane have to say that what we call Lean Accounting is remarkably simpler than what we call traditional cost accounting. I grew up as a cost accountant. I worked for companies like Lego and a typewriter company, believe it or not, some people out there may not know what that is. And a blasting products company and I worked for some unbelievable cost accountants and I was a pretty damn good cost accounting myself. But it seemed as if the only people understood cost accounting with cost accounts. And even there you you, you had a bell curve when it got to the CPAs of the world and the financial types. Cost Accounting scared them because they just didn’t. It was something that if you don’t really do it and live it, you don’t understand it. Well, well, therein lies the first problem. Nobody understands it. Okay. Secondly, traditional cost accounting Shane and Patrick drives on lean behavior. So here I come into Jake brake, which is the legacy company For dinner, where I came in as a as a senior cost accountant, manager, and eventually became their CFO. And as I got sent to Japan in the late 80s, and started working with Shingo Jitsu, and all of this work related as the foundation for dBs, the Danaher business system, I started seeing the things that we were doing in an accounting perspective, that were driving the wrong behaviors, okay? All the things that we measured and applauded ourselves on, were just driving us to go the wrong way, as it relates to Lean principles. So for example, I’ll give you two examples. And there’s many absorption accounting. Fundamentally, absorption economy means that I’m going to capitalize all my production costs into inventory. All right, and only expense them when I either sell the product, or if I Well, the other way it comes out is obsolescence. Right? If it’s if it’s spoilage, or whatever. So there’s an incentive for manufacturing to produce as much as possible, because their absorption variances will look favorable. Well, what does that mean? If I’m making products, A, B, and C, there’s no incentive for me to change over and get really good at change over to go to B. I’m just gonna make a bunch of A’s because my absorption variance is going to look really good. That’s one example. Another example, which by the way, builds inventory. And we know that’s one of the seven ways atashi Oh, no. I’ll give you another example. Purchase price variance to standard cost, which by the way, we eliminated all the standard costing, I’ll talk about that later. What’s the easiest way to get a favorable purchase price variance, if my if my standard cost is $1, let’s say for raw material, I tell the supplier Hey, I’ll buy a gazillion of them at 90 cents. And as a purchasing agent, I look really good. I got a 10 cent purchase price variance. Well, now I just file it just in time principals, I bought more than I needed. Okay, I’m going to end up scrapping a bunch of this stuff because I bought too much, or by design changes. And that component is no longer valid. I’ve got obsolescence, right. I also and this is something that people miss a lot on this whole purchase price variance. When I tell a supplier to make a lot of part A even though I don’t need it now. I’m stealing capacity from that supplier to make Part B. Okay. And now you say Well, geez, we didn’t get Part B from the supplier. So we couldn’t ship less because the purchasing guys had them batch Part A, and consume more their capacity in that regard. That’s a missing thing that a lot of people don’t think about. So again, just another one of those measures that are trying to do the right thing. In this case, purchase price variance, absorption variance, but drives absolutely 180 degrees, the wrong wing behaviors. So what’s the best thing to do in that respect, we five Vestas and we get rid of them. Okay. I mean, you know, we stopped doing it, right. And what we’ve done is gone more to actual costs, in trying to drive cost to the value stream or the sell itself to the product. Now, here’s another big difference, Shane, that us a lot of this has to do with how we treat overhead costs. Okay. And typically your traditional cost accounting process, take some arbitrary basis, like direct labor hours, machine hours, whatever, and allocate overhead costs based on that basis, which has absolutely nothing to do with, in most cases, the cost absorbed by those value streams. So in other words, if this is taken example, if I have a million dollars of fixed costs, let’s say building depreciation, it’s, it’s salaries, it’s insurance. It’s all this stuff, right? And I’m going to allocate it based on direct labor hours. Well, if I have a highly technical cell with a lot, a lot of automation, they’re going to receive less of that charge than a cell that has a lot of labor. It’s totally a disproportionate allocation of those costs. So the whole idea here is to drive as much of your overhead cost directly to the value stream that consumes that cost. All right. And we did that and we’ve reduced by about 80%. The amount of allocations. So what we ended up doing is charging things like maintenance tool room, all the related costs right to the cell itself. Not enough people had control their destiny. And all those costs, were as closely matched to the product costs as possible. In a traditional environment, you’ve got this overhead percent, you know, you guys know probably Patrick, from your engineering days, hey, what’s the overhead rate was 20 or 50%? And just throw that on there. Not even having any concept what that might mean. Right? Yeah, and that’s fair, right? And it means nothing. So now we can say, a none of these costs are being allocated their direct charge to the cell. And by the way, if they don’t make any sense, get rid of them. All right. So I can tell you about more war stories about how the accounting itself saved our company, a boatload of money. Okay. So those are some of the fundamental differences. So what

Shayne Daughenbaugh 10:48

I’m okay, I can appreciate that. So what I’m hearing is, if I had to put it in, in language that I’m familiar with opportunity cost, you mentioned, you know, using up an opportunity for part B, with getting all of this for Part A, the the unclean behavior of batching, you know, having to batch certain things and those kind of that that’s kind of kind of what I’m hearing, can you as as it sounds, to me, it’s almost like you’re trying to simplify the accounting process, in a big way. Is,

Mark Deluzio 11:28

is that accurate? Absolutely. Absolutely. And again, I told you earlier, it was embarrassingly hate. Tell me about Lena County. It’s so damn simple. It’s, it’s, it’s an embarrassing, almost everything’s there’s some kind of big mystery. Okay. And it’s not, it’s a lot easier than your traditional stuff you learned in college, and I learned on the job, you know, and, you know, there’s a lot of different traditional thinking. And, you know, I think you probably have probably heard me say before, the finance organization is usually a major reason why Lean transformations fail, okay? Because they’re standing there with their clipboards and their calculators, and green eyeshades. In the stands, while people are in the arena in the arena, finding the lions and tigers. They need to be in the arena with them because they’re part and parcel to the transformation. So a lot of people said, Well, Mark, what do I do when the finance guys come to me and want me to justify my lean initiatives? My turn is turned a question back to them, Well, maybe you can show me a model of how you justified your finance group. Okay, show me that. Show me how you did that. Because I don’t know how to do this. You’re the finance guy. So I’m sure you’ve done this with your own team. Show me how you justify that financial analysis that find financial analyst, okay? They can’t, okay. And there’s certain things you can’t justify with dollars and cents, there’s a certain things you can’t do. And so, so this whole business about I need to have accountability and a payback on every little thing I do with Lean is a killer, because you just possibly can’t do I’m pretty good finance guy. I can’t do that. I’d never be able to justify on paper, I can make some numbers up. I never be able to justify on paper, the value of doing five hours. Okay, there’s absolutely no way. Just like you can’t justify Shane going to the gym and spend 45 minutes on a treadmill. I want to know the data now that change in your body, but you can’t. Okay. So does that mean it’s the wrong thing to do? Absolutely not. So,

Patrick Adams 13:37

Mark, you talked about lean, lean accounting versus traditional accounting. And you use some examples from your time at Danaher, specifically, you know, looking at like, you know, material prices and maintenance and things like that. So that for a lot of our listeners, I think that resonates it, you know, there’s a large majority of our listeners that are in the manufacturing industry, I wonder about, you know, those that are in, you know, state local government or nonprofit organizations or health care, you know, does it is traditional accounting also, you know, incentivizing the wrong behaviors or contributing to the wrong behaviors in those industries? And is there a different way that accounting can be looked at in those industries? Or is it only, you know, the manufacturing industry, or

Mark Deluzio 14:24

or Oh, no, no, you know, it’s a good question, Patrick, and I’ll tell you this. The one thing that financial professionals have to get over the hump on is that how you organize your managerial reporting, does not have to be compliant with any GAAP or Sox compliance or, you know, financially, you know, accounting standards boards, it doesn’t have to be government compliant at all you can account on the back of a napkin if you need You as it relates to managerial accounting, the problem is we try to take financial reporting, and use it to run the business. And that’s a non starter, because the financial reporting that you get does not give you the granularity. First of all, it’s looking in the rearview mirror number one, usually three weeks late, but it doesn’t give you the granularity to make decisions. So, the first thing to do is get over the hump that your your managerial accounting does not have to be compliant. Okay, with with with law or anything else, you still need to do all that stuff really, really well. Because you have to report to the public or whatever it is, banks, whatever financial institutions, Wall Street, sec, okay. But as far as looking at the accounting in, in a, in a nonprofit, or in a service organization, the same theory applies, you really have to look at the numbers that you’re that are coming out of your financial system, and ask yourself, are they driving the right behaviors as it relates to my stakeholders? Okay, my stakeholders mean, well, the people I’m serving this are your nonprofit, well, the people who are benefactors of your, your nonprofit, are your customers, right? Your employees are your customers for the nonprofit. You’ve got donors who in a sense, are our customers or stakeholders? So am I doing the right things as those objectives I set for those stakeholder groups? Or are my accounting measures and reporting? Moving me away from that, and actually have me do the opposite thing? And that’s what you have to look at. So it applies there as well. Absolutely, yeah.

Shayne Daughenbaugh 16:48

So for those that, let’s say, traditional accounting, that are familiar with that, you know, bless their hearts, in, you’re mentioning something that, hey, you don’t have to worry about all of these things you just mentioned, like I imagine red flags are popping up like we what we were taught, we had to worry about all of this, you’re telling me we don’t can can you kind of bring that down a level a level and kind of explain to if you were as if you were speaking to someone who is traditional cost accounting, and working with, you know, standard costs, and all of those kinds of things, how that contributes to, and you’ve kind of mentioned it, but how that contributes to dysfunctional lean behavior, maybe within manufacturing, and and I love how Patrick said that, you know, in other services as well, like, what, how does this, like really steer us off the boat like we’ve been working? Maybe we’ve been working with with Lean for a while, we’re also using traditional cost accounting, what’s kind of the clash that’s happening in there in that sense?

Mark Deluzio 17:56

Yeah, you know, Shane, one of the things that the financial community has to understand is that they cannot lead with this, they have to follow the changes that get made in an organization. So for example, I had a company out of Florida call me one time, Hey, Mark, we want to do Lean Accounting. And I asked him like three or four questions, and said, You’re not ready for it. Because the organization was still working on MRP, work orders, all push manufacturing, they had no value stream set up. They’re still in functional departments. They were scheduling each operation independently, they didn’t have that single point schedule that pulled through the factory, okay? They were not set up to win in the accounting has to follow that. Okay? The Lean Accounting has to follow those changes. So to try to do this without having the organizational change won’t work. Now, the next thing and probably more importantly, is, or equally important, is you have to have an enlightened leadership team that understands why this is, and most leaders don’t have that experience. Now, I was lucky enough to have the air cover with heartburn. Who’s a good friend of mine, he was a group executive at dinner and George Kona Sager, those two guys gave me air cover. In in in in metal pipe, I got an unbelievable negative report from Danaher, as corporate auditor, who came in who was very friendly. And pat me on the back, hey, this is great. This is great, really like what you guys are doing. Our numbers were blown the cover off the ball. And then I got this negative report of how draconian our system was, Okay? And how it violated all these accounting principles. And this guy didn’t understand that. As I said earlier, the accounting principles don’t matter because I’ll give you one example. We charge actual cost to the cell. And one of the things I didn’t want to do is the whole purchase price variance concept I talked about earlier. So I was able to break down product costs by product for every cost category, whether it be labor, tooling, supplies, machine depreciation, whatever. Well, one month, this operations guys can mark my, my, my cost for tooling per unit went through the roof. I go, yeah, we’ll take a look at it. Well, he bought six months worth of tooling. But Mark, don’t you amortize that I’m not going to be using that. Over I’m not using all that six months worth of product this month. As for six months, I got a good deal on it. I will good the next five months, you’re gonna look really favorable. But no, this month, all six months? It does get in charge this month. But Mark, that’s not fair. I know. But that’s just the way it is. Right? And from a financial planning perspective, we will amortize it. Okay. If I happen to fall on a quarter, but not for a manager? No, I don’t want you buying six months with the tooling with by the way. And I was right, the the design change that tooling was going to be obsolete. Let’s go back to your supplier and negotiate a deal that you’re going to take one month at a time, or whatever it is. But no. So he went back and sent back for months and got a credit. And sure enough that design change that tooling would have been obsolete. Okay. So here’s an example where, no, I’m not going to let you do unclean things. Okay, and yet, my accounting did not match what we were putting in the financial statements that go to corporate net, go to Wall Street. But I didn’t care about that I was trying to drive the right behaviors. All right. And there’s a very good example. All right, so. But if you don’t have the understanding of your leadership, in getting through the heads of the financial guys, that your managerial accounting does not have to match your financial accounting, then you’re going to always hit your head against a brick wall. Alright.

Patrick Adams 21:56

So great, great insight. On that, I love hearing that. And I was thinking, while you were, while you were kind of wrapping up there, about the the the traditional way that organizations determine price for their products. So they they take their cost that is, you know, based on history, you know, they look at, you know, how much time it takes resources, all that stuff, they come up with some kind of a cost. And then they determine, Okay, well, we should be making x amount of profit. So they add their profit on to that, and then that gives them a price. Right? That’s interesting, and correct me if I’m wrong, but that’s how I would understand traditional pricing models. very simplistic, right. But in the Lean world, we we take our price that the market determines is the price based on the value that we’re able to provide, subtract the cost, and that determines our profit. And it’s our job to try to minimize reduce our costs in order to maximize our profit. And it’s it’s a different thought process around how we should be, you know, how our pricing model shouldn’t be set up. Was that is that something that you guys looked at at Danaher? Or is it something that you talk about in your book? What are your thoughts on that whole concept? You know,

Mark Deluzio 23:16

you, Patrick, you just hit on something that is something I’ve been fighting for 30 years now, okay. And in that whole market based pricing, versus a customer’s not going to pay you for you in efficiencies, and how they can make that decision by not buying your product because you’re overpriced, okay. There is a market value for what you have to offer. And this goes into another area, which I want to talk about. But but I’ve had this debate, time and time again. And when I actually do a, have a client, look at that, what I call a loss analysis on their quotes, okay? And we Pareto the heck out of that to figure out how all this works, and why are we losing? The easiest thing that a customer can tell you is that your price was too high. And many times I found that is not really the reason why they’re not doing business with you. Okay? It’s because your quality is lousy, your lead times are too long, or whatever. But it’s easy for them to say your price is too high. Right. But in those cases where price is too high. I’ll ask the question, Are we are we market based pricing to your point? No. Without a doubt, 100% of time say yes, we are. And then the conversation will will ensue. And before you know it. Yeah, the reason we lost it so the costs were too high. A minute. I thought you just got through saying you’re not pricing based on cost. Well, we’re really not but they are okay. And so you just hit on something that’s a real big deal out there, that everybody expects customers to pay them for the Your inefficiencies. And if your costs are 12%, higher than your competitor, everything else being equal. Now, one of the things I want to talk about is, even in a commodity product, which I would define as the only differentiator is your price. You can, you can beat people by differentiate yourself, I don’t believe there is such thing as a commodity, if you can provide best quality, markedly the best quality and lead times and on time delivery, you’re just now delineated yourself from everybody else, and you’re no longer a commodity, even if the product itself is viewed as a commodity, right? Because availability is a big deal and a lot of these things. So we had a business and I talked about this on different podcasts that was a commodity product was a temperature controller in England, it was new acquisition. And we went from 28 days lead time to three days. Managing director didn’t think we could do that. But we did. We did in about nine months. We took them Patrick from 30,000 units a year to 110,000 units, because we have the best delivery. And the best lead times in our distributors did not have to carry all the inventory. And they get measured on and glimmering gross margin return on investment. What’s your biggest investment? Inventory? Okay, so guess what they wanted to buy? And we’re competing against Honeywell, and Siemens, some little company in England, and we’re winning, okay? Because they did not get the service from these bigger companies. Right. So even in that case, you can win by being the best guy out there with lead time and quality. Okay, sure. And service, okay. You know, but you just hit on something that everybody conceptually would say they’re doing. But they’re not right, because the first time when they look at what the cost of this product is, as you’re talking about price, you know, they’re not doing it. Hello,

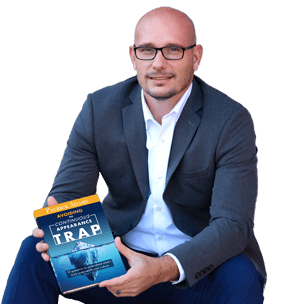

Patrick Adams 27:01

everyone, I am sorry to interrupt this episode of the lean solutions podcast. But I wanted to take a moment to invite you to pick up a copy of my Shingo award winning book, avoiding the continuous appearance trap. In the book, I contrast the cultures of two companies I work for. And though each started with similar lean models, one was mechanistic and only gave the appearance of lean, while the other develop a true culture of continuous improvement. The contrast provides a vivid example of the difference between fakely. And truly, you can find the book on Amazon, simply search by name, or the title of the book, you aren’t a reader, no worries, the audiobook is also available on Audible. Now, back to the show. Absolutely. And that’s, I think that is definitely an issue for a lot of companies. You know, to your point, they’re overpriced, because they’re pricing based on all their inefficiencies and all the issues that they have, rather than looking offering, increasing the value for the customer and making sure that the customer understands the value and will will be willing to pay more. So there’s yeah, there’s like this, this script, the script needs to be flipped it with an understanding and that way, I just remember a company that that I worked with, I think I’ve talked about this before, but they were competing for, for a job with a with a with one of their customers, and their price was way too high. And they’re like, Hey, can you guys come in and look at this and figure out why, why we’re priced so high, and in comparison to our competitors. And so we went in and took a look at this assembly line, which had, I think there was like 2122 people in this little, you know, maybe 10 foot by 20 foot assembly line, you know, 2021 22 people that are, you know, packaging, assembling, doing all this stuff. And, and I’m like, you know, wow, that’s, that’s a lot of people for the output that you have going here. And we did some time studies. And we, you know, we observed the process for a while and, and ended up that was the recommendation was, you know, we need to figure out how to do this with with less people, this particular job and they weren’t willing to do that. Unfortunately, they lost that that job, but that’s what I was thinking about that and thinking to myself, that you first you have to look at the inefficiencies that you have the waste and try to drive that out. Reduce that so that you can do you know, do that that specific example if we could do that with half the people. Now all of a sudden that allows us to, you know, maybe have a you know, more profit in that scenario and still price it maybe at a you know, where we need to in order. But but, you know, we have to make sure the value is there. We have to reduce our own inefficiencies and then you know, the profit will come.

Mark Deluzio 29:51

But yeah, when he said when he said, We want to find out why our price is too high. My first question would be well, who set the price? Right now? You did, right? And the reason why it’s too high is because you set it too high. That’s why it’s too high. You know, and what people don’t understand is that you can’t when you don’t get a sale, that’s zero, you cannot deposit that in a bank. It’s zero, you lost the business, and it’s gone. So do you make a lower margin? Because again, I can’t take percentages to the bank, either gross margins, let’s say, but or do you, you get the business and continue to work on your cost position to make more profit, because you know, it’s otherwise zero is zero. And that customer goes away, the probability of getting that customer back is really, really tough. So

Shayne Daughenbaugh 30:45

so how, Mark, you know, in talking about this concept, what what I’m thinking about is, like, like, for me, I’m just kind of thinking consultants are those that are in the Lean community lean practitioners? How did they come about that? How do you how do you make this suggestion? Is there kind of a side you’re to come in on, when you have such a strong history of standard accounting or cost accounting, traditional, whatever, however you want it, you want to name it? There’s such that, that strong Thurber to hold tight to this, you know, especially when it comes to money, people want to hold tight to those reins? In the maybe it’s the illusion of control? How do How would someone like myself? Or maybe, you know, if they’re embedded in the company, as as a practitioner? How did they How did they start to bring this up and make this possible?

Mark Deluzio 31:44

Well, you know, I don’t think lean accounting or change your accounting systems are any different than, for example, going from batch to cube a batch and queue to one piece flow, okay, and reconfiguring your lines and pulling equipment together and, and creating cells and value streams. That’s a remarkable change, because you got to remember, if you go back in history, Shane, the, this whole thing, the MRP, work order the IV yt, batch and queue production, all had to do with the accountants trying to control this asset called inventory, which is a very volatile inventory. asset, right? It moves every day, it changes every day, there’s a lot of exposure to it. And if you get it wrong, you missed it, your your financials, and you know what happens then. So what did we do we created stockrooms, we created checkpoint Charlie’s that you have to check it in and out. We inundated the factory with unbelievable amount of transactions, okay? Which are zero value added to subtract it from going from one part to another part of the factory, and then back and back and back. And, okay, so, all of this has to do with that. The accountants attempt to control this asset called inventory. Well, when you get to a point where inventory is inconsequential to your balance sheet or to your profit and loss statement, you no longer have to worry about it. Okay? As a matter of fact, once we, you know, evolve at Jake brake. I got to a point where two years in a row, I didn’t have to take a physical inventory by the auditors. Okay. What ruins that story is auditors auditors were Arthur Andersen and if you think about Enron, those Oh yeah, no wonder they let you do it, right? No, I always joke about that. But no two years in a row, because our inventory was inconsequential. And they were so show me your perpetual inventory, our inventory moved too fast for any inventory. To be able to document on some piece of paper, okay, if you want to know what we have go out and look at it, because it’s moving while you’re standing there. Secondly, we back flushed wall to wall. So what is back flushing, I go into all the different levels of my bill of material. And I make them phantom levels because you still want the integrity of the of the sub assemblies for engineering purposes, and for procurement purposes. So we didn’t flatten the bill, what we did was made those levels, those sub assemblies, what we call phantoms. When we we had to inventory transactions. When we ship the product, we back flush all the materials based on the bill of material. And when we received raw materials, those are only two inventory transactions that we had everything else in between zero. Okay, so we no longer had to have production control clerks typing in a bunch of transaction tickets. Okay. And remember all that buildup of inventory we didn’t have it, so I didn’t have to come for a high working process and labor and overhead inside. So again, guys, we backflush from all the while we had to inventory transactions. So when we shipped it to the customer, that was one inventory transaction, and that would back flush all of our components all the way through the bill material. And the other inventory transaction was when we received raw materials. That was the only two, we didn’t have production control clerks typing in a bunch of transactions, and then reconciling all the errors. And in all that stuff, we didn’t need to do any of that anymore. It added zero value to do that, and our inventory values were so low, that if you really wanted to see what we had, just go out and look at it, it was all virtually labeled with very clear, and you can actually see it you can actually see it moving, you know. So that was the idea. Well, why do we have to account for it? In the interim in working process? If it’s a inconsequential and B, we got control over it? Because it’s right there. I put my arms around it. I don’t need a report to tell me I don’t have something. Okay.

Shayne Daughenbaugh 36:02

So, so to answer to answer that question, are you saying that it’s actually simpler than I’m making it out in my head? If lean has done well, in the organization, if we’re really bringing in those kinds of principles, then the accounting side of things will actually be even, maybe, maybe simple or easy to marry that up with, just because of how we’re, we’re working, you know, in the processes that were doing accounting could easily follow. Follow along with that, that yeah, in

Mark Deluzio 36:37

like I said, embarrassingly simple. That’s the crazy part about this, okay. But it takes a what isn’t simple is the big mind shift, such mind, mindset shift that you have to make, especially from the CFO and the finance, guys, because all they know, and you gotta remember, financial, people are afraid of cost accounting for the most part, okay? They don’t understand it to begin with. But now Now you’re SM that change something that they don’t really understand. Okay. And that’s, that’s kind of hard. And, and the good news was, I had our burn, George corner secret, Bob Pentland, who was an unsung hero at Jake breaking that down or her who was a VP of Operations, that were just applauding me all the way through this thing. Okay, we got rid of standard cost altogether. standard cost? How many times have you been in a variance meeting? Where they’re explaining not their performance? But they’re explaining why the standards wrong? Okay, well, the reason why we’re negative because the standard is wrong, right? I’m gonna spend time doing that. I mean, come on, guys, you know, so we looked at total cost trends are my cost improving, that’s what we’re looking at. Okay. Because I could set a let’s just say I had a raw material item that cost $1 on January 1, and it was going to be, you know, by the middle of the year is going to turn to $1.50. With a price increase. So I might set the standard at $1.25. Well, the first half of the year, I’m going to be favorable. The last step that you’re going to be unfavorable. Now I gotta report on out every month. Okay, well, maybe maybe I am unfavorable. But it’s being hidden by this average standard that I said, The Thing, Thing about a standard cost is a budget for a product. That’s what it is, which includes labor, material, labor, and overhead. It’s a budget. How many budgets have you guys set whether it be at the state in Nebraska, Shane, or any other client that you guys might have? That were exactly equal to your actual costs? Never. Okay, never. And so. So when you when you look at a standard clause, it creates such minutia and does not really you know, support Patrick, the, the PDCA, the Plan, Do Check Act mindset. It’s more along the lines, what it really Foster’s is, plan, do check, explain. Plan, Do Check Act. Okay. Right, right. I mean, really, that’s what it does. And it’s a big waste of time, is and

Patrick Adams 39:20

you’ve hit on standard costs. Just kind of it’s woven through the conversation. And I want to, I want to kind of pause on there and maybe ask you to expand a little bit. I want to talk specifically about those organizations that are out there that have already embarked on their Lean journey there. Maybe they’ve been on a Lean journey for a few years. Maybe they just started, but they they haven’t looked at their accounting practices yet. In Do you think that I mean, standard accounting, using standard costs? I mean, is it possible to be successful on your Lean journey if you’re still using standard costs and I mean, what are your thoughts on that? Yes,

Mark Deluzio 40:01

yes, it is, but you won’t be as successful. Okay, and because you’re gonna waste a lot of time on that, and I’d rather have my accounting group be navigators than historians. Okay, that’s really what you’re talking about. Okay. So if I spent a lot of time reconciling and putting together standard cost in the final analysis mean nothing, then, you know, here’s the other thing, guys, you know, think about just your daily lives. And how you guys would I always like to go back to what we would do personally? And, and would we do these things? If it was own personal, you know? Well, first of all, you wouldn’t go off chain and buy six months worth of groceries? Correct? Hey, where are you going to storm? The it’s a cash flow issue, even if you save money? Well, we do it in business. Right? I’ll tell you a quick, a quick little story here. I was with the CEO, and the CFO of this multi billion dollar company. And we were walking through one of their plants down in Arkansas. And as I’m walking through the plant, I said to the CFO, hey, how do you guys compensate your people out here? They said, everybody gets measured on machine uptime. Sure enough time, okay. So right there, red flags went off, you know? And I said, Well, why do you do that? And the CFO said, Well, we paid a lot of money for this equipment. We want to make sure we get a return on investment. That sounds reasonable, right? That doesn’t sound like anybody would argue with that. So I said, Well, how do you take it take return on investment to the bank? Because Because what because what was happening here is they were not doing frequent changeovers. Like I said earlier, they’re all making product day. No incentive to change over to be there. Customers were calling they were losing business. Because they weren’t delivering B and C and D. They kept making a the obsolescence went through the roof. They weren’t doing preventive maintenance. Nevermind TPM, but just preventive maintenance, because that took time to take away from their measure their compensation measure. And I said to the CFO said, Hey, by the way, you just told me the other day, you bought a brand new car? He goes, Yeah, I did. He said, I bought a Lexus. That’s a good choice. They’re good cars. I’ve owned them before, you know, even though I’m a BMW guy. And I said, it’s a great car. So let me answer your question. I said, you paid a lot of money for that. Right? He goes, Yeah, pretty expensive, but it’s worth it. resale value. Okay, good. When you go home tonight, are you going to drive the car around the block a few 100 times just to get utilization out of it? Well, why would I do that? I don’t know. You’re the one that told me to do it here. Why would you not do it yourself tonight with your Lexus? And the answers are obvious, right? Why he wouldn’t do that. Right? And he finally said, you know, I never heard it that way before I go, Look, these machines are sunk cost. You can’t get the you can’t get their costs back. Okay? No, I’m not saying it’d be foolish and how you utilize his equipment. But we should be trying to make product detect time and actually try to mirror our production plan as close as possible to our demand plan. Okay, when you make all A’s, that’s not how your customers order. They ordered a B’s and C’s, okay. So then in order, the way you decide to produce, so So now you guys got to get better with changeovers be more flexible, you know, and all that kind of thing. This is where hydrocal level scheduling comes in, is down the bottom of the TPSS. Right? See how all this stuff ties together. The bottom of the TPS how standardized work and consent? Well, I can’t really marry exactly my demand plan to my production plan. Okay, well, why not? Let’s let’s understand why. And there ensues Mike Tyson. Sorry. Okay, maybe it’s a quick changeover causing them to need to do maybe it’s our Think about standardized work and mixed model production and all that good stuff. Right. But this all ties back to that, you know, and it’s hard to talk about any one of these things in isolation because it’s one Lean is one big Venn diagram, right.

Patrick Adams 44:16

I love I love that and the it kind of ties back to what we were talking about earlier, because so many companies are just they just, they just think like, well, this is these are our costs, this is this is what it it is what it is, this is the way you business this is our changeovers are two hours long, our, you know, machines run at 50% OEE, or what, you know, whatever. That’s it is what it is. So let’s base all of our business on that. You know, is that the mentality or is it what you said? You know, why are changeovers an hour long? Of course, I wouldn’t want to end You know, when we talk to setup taxing operators about increasing the number of changeover So we can reuse inventory. They look at us like we’re crazy because they’re like, exactly going to increase the number of to our changeovers. You know how, how terrible those changeovers are? Exactly. So you can’t think about it that way, you have to start by thinking about how can we improve the changeovers? Let’s reduce these down, let’s start running some sweat events and get these down to under 30 minutes and remove some of the headaches and the problems of you looking for tools and having to walk over to the other side of the plant 15 times during a changeover. Let’s get rid of some of that. Now we have shorter changeover and as an in then it’s a lot easier sell to have a conversation about what increase changeovers might look like.

Mark Deluzio 45:37

There’s, there’s a high incentive for a NASCAR driver or Formula One driver to have like a three second changeover. Okay. Because we got to get that operator back on its work sequence, which was the racetrack I like to use analogies, and one of the examples I would use on changeover. And I have used before is I’d say, and people can understand well, why, why why don’t have to do more Change Overs, because the old Ollie white EOQ measure says do less right, and optimize your economic order quantity. Well, if you’re not thinking about an economic quantity of one in one peaceful environment, then you’re thinking about the wrong way. Not that you’re going to get there overnight. But the example I like to use is I’d say to, to anybody, for that matter how many people had a barbecue in their backyard. And they all raise their hand and okay, you’re making hot dogs and hamburgers. You got 20 guests, friends and family. How many of you guys just make all the hamburgers first? on the grill? nobody raises their hand. Oh, that means that must mean you do all the hotdogs, right? No, we put hotdogs and hamburgers on the grill at the same time. Well, why? Because we want people eat together. Some people, we have demand for hotdogs, we have demand for hamburgers. And if you’d like me, I like both. I’ll have one of each. But you know, you don’t want the people who want hamburgers to eat in isolation from the people who want hot dogs. You want them to eat together? Well, show me a work. Show me an order Jesus machine makes 12 parts. There’s eight of them on here that they’re asking, and they’re all asking for these on the same day. So why are you making one part per week and changing over on the weekends. Now that we just took your change over time by 75% in three days, by the way, you should be able to make each one of these parts every day. But not in the same quantities. Because your domain is different. Right. And so you bring it back to everyday life. And it starts making sense to people. You know, but we’re incentivized the wrong way, Patrick and Chang to not to do that. Because you mentioned Oh II to me, oh II, I don’t like that measure, because it has the same effect as absorption accounting, exactly the same effect, I get the best OEE I just run my equipment. And I don’t shut it down. And I know to Change Overs, right? That’s how I got my best OEE. Now if you really, if people really understood OEE, they would know that that’s not the right way to think about it. But that is how most people get measured. And so that’s the best way for me to get my UI is just run a bunch of stuff. Yeah,

Patrick Adams 48:09

no, I appreciate that. And it is it’s it’s a hard subject for those of us like Shane said earlier that don’t you know, don’t live in the accounting or the financial side of things. But I appreciate the simplicity of how you’ve presented it and kind of broke it down. Like you said, very, very simple concepts. And I love the tie back to real life. The grill example is a perfect example. We were were on grilling to for my family for my family and friends that are here, they’re my customer, I want to make them happy. And so I want you know, in the same way in our within our companies do I want to have one customer waiting, while the other customer while I’m building stuff for two other customers that aren’t even going to get it for another two months. Kind of batch right now I want to make what the customer needs and make sure that they’re happy so that we’re maximizing the value for the for the customer first,

Mark Deluzio 49:06

you’re gonna pay for this another another thing you bring it up here is this is why this has to be an enterprise endeavor because, you know, a salesperson who and I had this experience with many clients, but they get compensated on shipments. Okay. So instead of going to that customer and saying, Oh, you just ordered 50,000 Knowing that customer needs 10,000 month for the next five months, the order goes to manufacturing for all 50,000. Right, which obviously violates just in time principles and all that good stuff. So this is why the enterprise endeavor that’s mirror and Mary that that causes right, then it causes a bunch of muda neurobion unevenness merely being unreasonableness, if you will, and overburdening and if you think about it. The sales group now is not in concert with what’s going on, on on the factory floor. So here you got guys out there trying to live a load and one piece flow just in time. And they come in with a batch order like that. That violates Justin time principles. Okay? So an easy way to change that is, is to change the sales compensation and base it on orders not based on shipments, okay? Because this is the case where anytime you try to optimize a function, in this case sales and have that function when most likely you’re going to sub optimize the enterprise. And that’s not good. So everybody has to be in concert with the same set of objectives. And otherwise, you’re you’re not gonna win. Sure, you know. And so

Patrick Adams 50:42

that makes sense. And obviously, this is this is also a very heavy subject, too, with a lot of intricacies and details and different pathways that we could go down. So we almost need to do like a four part series on this, you know, and get into some of the other details that go along with it. But

Shayne Daughenbaugh 51:00

should our questions. Right, right. I

Patrick Adams 51:03

know, that’s the problem. We’re kind of out of time here. But, Mark, I appreciate you coming back on the show. For the for the second time, we’d love to have you back again to talk you know, more.

Mark Deluzio 51:14

Absolutely. Love to help you.

Patrick Adams 51:16

But before we close up, though, Mark, I know we talked about this last time, real quick. Can you just give our listeners just talk about the nonprofit, the nonprofit work, the charity work that you do with veterans and just kind of put a plug out there for that real quick. Yeah,

Mark Deluzio 51:33

and I know that you’re a veteran. Shana, you’re a veteran? I don’t know if you? Well, I know we have a marine here. I don’t want to say you were a Marine, because you always are going to be one. That’s right. And we thank you for your service. But yeah, maybe mid may or may not know may or not, may not know, I’m a gold star father, I lost my, my son got killed in Afghanistan in 2010. And as I started, and my other son served there at the same time, by the way, they were both in the infantry, they both left CPA firms to go fight in the infantry did not want to become commissioned officers. So the NCOs anyway, long story short, my son was killed in the 2010. In Afghanistan, he was shot by the Taliban, they got ambushed. But as I started learning about the plight of our veterans coming back, and especially those trying to enter industry, or, you know, corporations and all that. And you know, better than me, Patrick, the military is very regimented, very standardized, very black and white incidents of your responsibilities, who you report to, everybody knows, if you didn’t get it done, it’s very obvious. And they come back into the supposedly well oiled corporations, at least that’s what their CEO say, and they see a see a gray, okay. And they have a lot of trouble functioning and as a trust issue, too, because the people that they were with, even if they hated the guy next to him, they know that that person had his back. Now you come back here, and you got all this politics and games. And the trust issue to me is probably the biggest issue that that veterans have, and I can’t fix that. But what I can do is help them either navigate their careers, or many of them come to me and say, hey, I want to start a business. And first thing I do is I try to talk them out of it, okay to make sure they really have the, the DNA to do this. So my organization, it’s not a nonprofit, because it’s it’s I don’t take any money for it’s all just based on time, and help and I write strategic plans and financial plans, I’ll go to a bank and get a loan and make an investor presentation or whatever it is. But it’s called Brave br AV E. And it stands for business reviews in advisors, for veteran entrepreneurs. And the website is for the brave.org. The number for the brave.org in what I try to do is to help our veterans transition because, you know, I’m stealing this phrase, but as you know, Patrick, I think we do a pretty good job helping our military put on the uniform. But as a country, we do an awful job, helping to take it off. And and that goes from health care to the veteran. I was just on a call the other day with a marine from Vietnam is a good friend of mine, I ran for Congress. I’ve met a lot of good people, that and people are just dying in our VA hospitals based on negligence and, and and in some cases, corruption. And I just look at how we treat our veterans after they get back. And the only time you really hear about it is when politicians are running for office. And then it gets forgotten for two years. The homeless is insurmountable the suicide rate is, as I’m sure you No and probably no people who are no longer here. I just think our country does a horrendous job at taking care of our veterans. So I asked myself after my son died, you know, I didn’t serve I missed Vietnam by about a year. And not that that’s an excuse, but it didn’t serve. And I said, Well, what can I do? You know, to offer help for them, right? Cheese. God’s given me a bunch of gifts. I know they’re on loan. They’re not me. The experiences I had been at the right place at the right time, but Danaher, a Jake brake working for guys like George Conan, sacred art burn, how the hell lucky can you have gotten right? And so I know all these gifts that I got the experiences and even the mistakes were all gifts. And if I don’t do something with those gifts, then to me that’s a sin. Right? Yeah, that’s why I do it. So

Patrick Adams 55:56

yeah, love it, love it. Well, we’re going to drop a link to that in the show notes along with a link to links to your books, and your your your website. So we’ll make sure that all that is in the show notes but you bet you definitely raised a couple good boys. They’re so good on you there and appreciate what you’re doing with braved

Mark Deluzio 56:15

Yeah, what Stephens the one that got killed. His name was Steven, he was 25. Scott was 20 at the time. The only feeling I have is he was he grew up to be a Yankee fan. Okay. And I’m a diehard Red Sox fan. Okay, so that was one failing in life as a father anyway.

Patrick Adams 56:38

All right, Mark. Well, we’re gonna close up here. Thanks again for your time again today and just appreciate you and if anybody has any questions, feel free to reach out to mark on LinkedIn or at his website. I’m sure he’d be happy to answer Yeah,

Mark Deluzio 56:52

the best way I’m not on LinkedIn. When I was running for Congress they kicked me off for telling the truth about a couple of things. But you can get me at Mark at lean horizons.com A mark Dr. luzio I’m sorry, Mark Dr. Lucio at lien horizons.com be happy to answer your question. You guys want to change you want to come back and do some more more follow up on this. We have to come back to you guys. So love it.

Patrick Adams 57:16

We’d love to have you on for sure. Thanks so much for tuning in to this episode of the lien solutions podcast. If you haven’t done so already, please be sure to subscribe. This way you’ll get updates as new episodes become available. If you feel so inclined. Please give us a review. Thank you so much.

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

0 Comments